Update

This newsletter used to be called Dry Spell. After some time away, I’ll be sending it out quarterly, and expanding what I’ll write about here. In addition to writing about canoeing, I’ll be including reflections on nature, old houses, archival research, and writing.

I like to follow my current interests backwards through history. Right now that’s canoeing, parenting in nature, native plants, residential architecture, and old cookbooks. I spend a lot of time looking at old letters, diaries, maps, newspapers, and scrapbooks. I weave my discoveries into short stories, essays, and larger works.

But I’m a slow writer, and in the meantime I want to be better at showing and sharing my work.

Please feel free to unsubscribe if this is no longer something you’re interested in. But if it is, thanks for reading, and please consider forwarding this email to a friend you think might enjoy my writing.

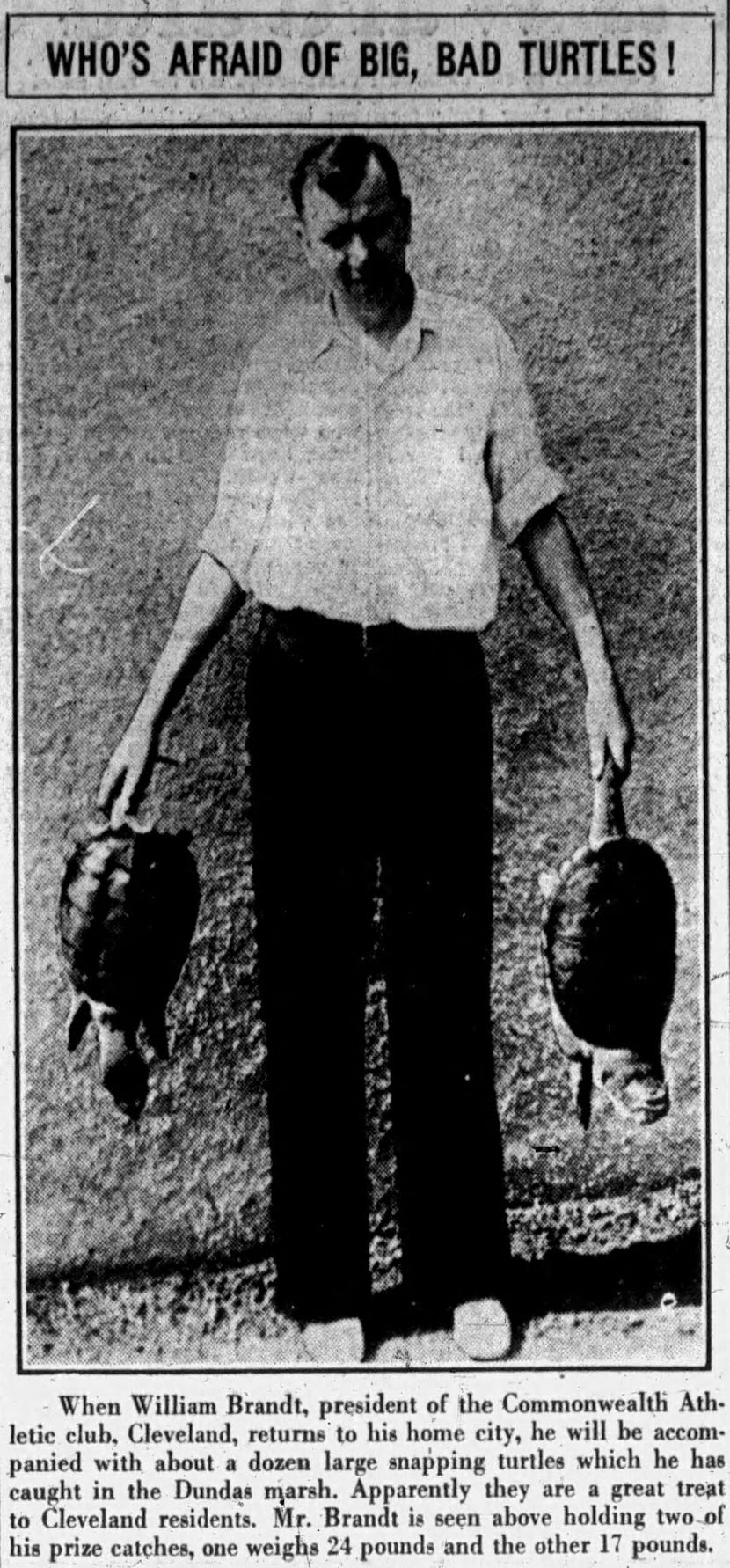

Turtles: “they are a great treat”

I went canoeing with my friends on the marsh a few weeks ago, my first paddle of the year. As we searched for turtles sunning themselves, I considered the ways our relationship to turtles has changed in the 234 years of recorded history of Cootes Paradise marsh. Isn’t it strange to think that locals used to catch turtles in these waters to eat?

I saw Midland Painted Turtles perched on logs, with dark shells rimmed by red or orange markings, as well as Northern Map Turtles, with fine yellow lines on their heads and limbs. Some dropped into the water as our canoe approached, others continued to soak up sun.

It’s hard to imagine them as ingredients. Turtle soup seems like a long-ago, far-away culinary creation, but once upon a time it was served in Hamilton and it was made from local turtles.

And once upon a time there were seven species of native turtles swimming through Cootes, but now there are four, and they are all species at risk.

*

When Elizabeth Simcoe visited the area in 1796, she described Cootes Paradise as a “marshy tract of land” that “abounds with wild fowl and tortoises.” I assume all seven types of turtles were swimming around Cootes at that time.

She ate one for dinner.

Two days later she wrote, “I found a pretty small tortoise, but boiling it took off the polish from the shell.”

*

It’s turtle nesting season now, through to the end of July. Female turtles migrate away from the marsh to find a dry, sunny spot to lay their eggs. Royal Botanical Gardens, the organization that manages the marsh and surrounding lands, asks the public to report any nesting turtles on their lands.

A big part of Cootes’ history is the shift from the marsh being a place that people lived, worked on, or ate from to a place of conservation. People lived there as a part of the Boathouse Community, and along with others, they hunted and fished to make a living, and ate the fish, frogs, squirrels, game, and turtles that also lived there. City planners, politicians and conservationists slowly worked to make the marsh and surrounding lands a protected place for birds and animals, as well as a tourist attraction and transportation route. By 1927, birds and wildlife were given legal protection, though the people that lived and worked there were displaced soon after.

*

A survey of mentions in The Hamilton Spectator shows reference to turtles as food from the 1850s through to the 1980s. They were advertised as high end fare, with turtle soup was on the menu of inns and taverns 1850s-1880s. In 1899, the Ramblers’ Bicycle Clubs of Hamilton and Guelph held an event at the Royal Hamilton Yacht Club, during which the yachtsmen treated them to a turtle soup supper: “About 100 cyclists were present, and they were entertained most royally. One of the best turtle soup cooks in Canada (W. Williams) had charge of the cooking. Seventeen turtles were used, one weighing 28 pounds.”

Turtle soup was described as a staple in North End homes. The Modjeska Hotel, a fixture at James North and Wood Street East for the first half of the twentieth century, was known for its soup made from local turtles.

A headline from 1937 reads: *“Clevelander Dead Set on Emptying Dundas Marsh of Potential Soup.” Though after 1927 it was unlawful, a man visiting Hamilton took as many snapping turtles as he could catch home to Cleveland for fellow members of the club he belonged to. “His hunting grounds are in the Dundas marsh and he told the Spectator this morning that it was full of fine turtles. Early this morning he set out his lines baited with pieces of meat and to-morrow, shortly after dawn, he will check up on his catch. Starting two days ago, he has to date caught six of the reptiles, ranging from 24 to 12 pounds in weight.”

In a 1956 local news story I can’t believe earned inches in newsprint, four men were fishing in Freelton and found a forty-pound Snapping Turtle. Their wives wouldn’t let them keep it. “The Chinese restaurants had no plans for making turtle soup and the SPCA told the men to take the thing back where they found it.” They released it into the Bay.

In 1967 one man tells a childhood story about four kids catching a giant Snapping Turtle. After their mothers refused the turtle entrance to their homes, they earned 75 cents selling it to a Chinese restaurant on King William Street. Almost the same story as the four men from Freelton, really.

The last time the paper makes reference to locals eating turtles was 1987, when The President’s Club served turtle soup as part of a historic banquet for McMaster University’s centennial.

*

What does turtle meat actually look and taste like? Scalding removes the reptilian skin, leaving two sizable pieces of meat: the tail and front legs, and the front legs and neck. Jack Hitt, in Saveur, describes the meat as savoury, sturgeon-like, more similar to trout than salmon, with a bright, clean and meaty aroma. I looked up turtle soup recipes and was surprised to see contemporary American sources offering recipes with no caveat. Soup ingredients include turtle meat, butter, chopped onions, bell peppers, celery, and garlic, seeded tomatoes, Worcestershire sauce, lemon juice, sherry, parsley, and chopped hard-boiled eggs. The earliest recipe I found in Canadian cookbooks was from Practical Cookery, published in Montreal in 1910. It begins with the jarring tip: “The easiest way to kill a turtle is to tie it by the back fins with a string, and let it hang with its back to the wall.”

My brain snags on the phrase turtle meat. I picture the turtles in Cootes, their wet shells glistening in the sunlight as they lay across logs, their tiny limbs and outstretched neck; nothing about that hard and soft green body reminds me of food. But meat is a cultural construct, what animals we consider eating and which ones we don’t. In North America we used to commonly eat oxtail, rabbit, mutton, pheasant, goose, wild game. After the Second World War, the rise of factory farming meant that variety had dwindled to chicken, pork, and beef (Saveur).

As recently as 1975, a wildlife field guide started a species description for turtles with its suitability as food. The Diamondback Terrapin entry begins with: “Most celebrated of American turtles. Their succulent flesh, when properly (and laboriously) prepared, rates high on the gourmet’s list.”

*

In 1927 the provincial government issued an order that under the Ontario Game and Fisheries Act “it shall be unlawful to hunt, take, pursue, kill, wound or destroy or have in possession, any bird or animal,” and designated the Cootes Paradise marsh a wildlife preserve. But, as evident by the Clevelander who harvested Cootes turtles, this was not always enforced.

Ontario’s original Endangered Species Act passed in 1971, and was strengthened and expanded in 2007. The culture changed over time, and appetite for turtle decreased.

But now the current Ontario government has weakened the protection of endangered animals by passing Bill 5. The 2007 Endangered Species Act has been feebly replaced with the new Species Conservation Act, which gestures towards conservation and protection, but only as far as those goals don’t impact development. (For more on this, see The Narwal). Our eight native turtles, four of which live in Cootes, are even more vulnerable.

*

Hatchling season stretches from August to October. Some turtles even spend winter in their nests before emerging in the spring. Most won’t reach maturity; for every 1,400 Snapping Turtle eggs, only one turtle will survive to adulthood. They’re a species at risk because of those odds, but also because of human behaviour, such as roads across their habitats. Humans have looked upon nature as a limitless resource, every turtle a soup. And now with the passing of Bill 5, every turtle habitat is a potential site for development.

There’s an area west of the marsh, where the old canal and Spencer Creek flow out and in between them runs an 80-km/hour highway between Dundas and Hamilton. For as long as I can remember there have been little plastic “Dundas Turtle Watch” signs rippling in the wind on the median. They list a phone number to call if you see an injured turtle, or one in imminent danger.

A week ago, in the car with my family driving back to Hamilton I saw a snapper the size of a dinner plate on the shoulder of the road. After all these years of looking and never seeing one, I felt I might have conjured the turtle with my recent research. Perhaps if we didn’t have a three year-old and a 9 week-old in the car, my husband and I would have turned back to move the turtle out of harm’s way ourselves. Instead, barreling towards the chaos of bedtime, I called the hotline and someone was dispatched to save the turtle.

Hopefully that turtle lived. At least it won’t end up as soup.

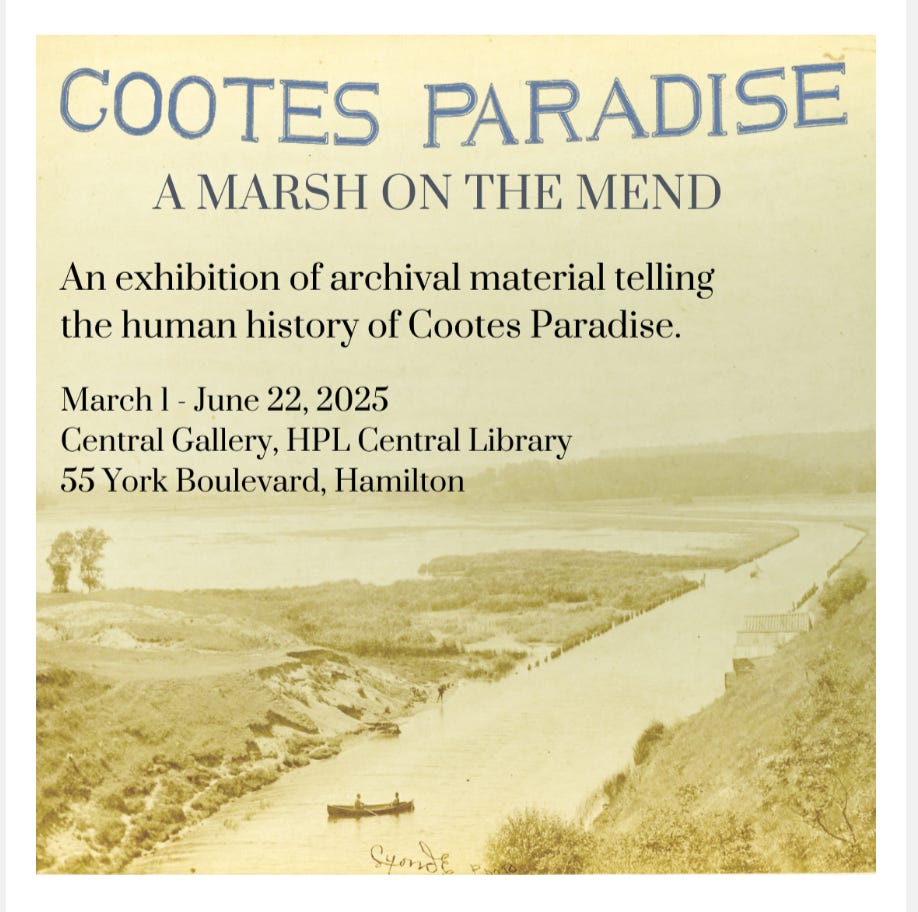

Cootes Paradise Exhibit

If you’re in or around the Hamilton area, I worked on an exhibition at the Hamilton Public Library, which is up for another week:

Cootes Paradise: A Marsh on the Mend.

An exhibition of archival material telling the human history of Cootes Paradise.

Cootes Paradise marsh was once a healthy, biodiverse wetland. Through archival material in the Local History and Archives collection, this exhibition explores the human impact on the marsh from environmental damage beginning in the 19th century to recovery efforts today. The treatment of the marsh has reflected the values of the people of Hamilton over time, including how it is described: a dense watery bog, a resort of wild fur animals, a marshy tract of land. A gathering place. A shallow muddy lake. A paradise.

This exhibition runs March 1-June 21, 2025, in the Central Gallery at Central Library. Also, the exhibit had some coverage in The Hamilton Spectator.

In addition to learning about the history of Cootes Paradise, I learned a lot about exhibit writing and design! I am grateful for the opportunity to learn and collaborate with my talented colleagues.

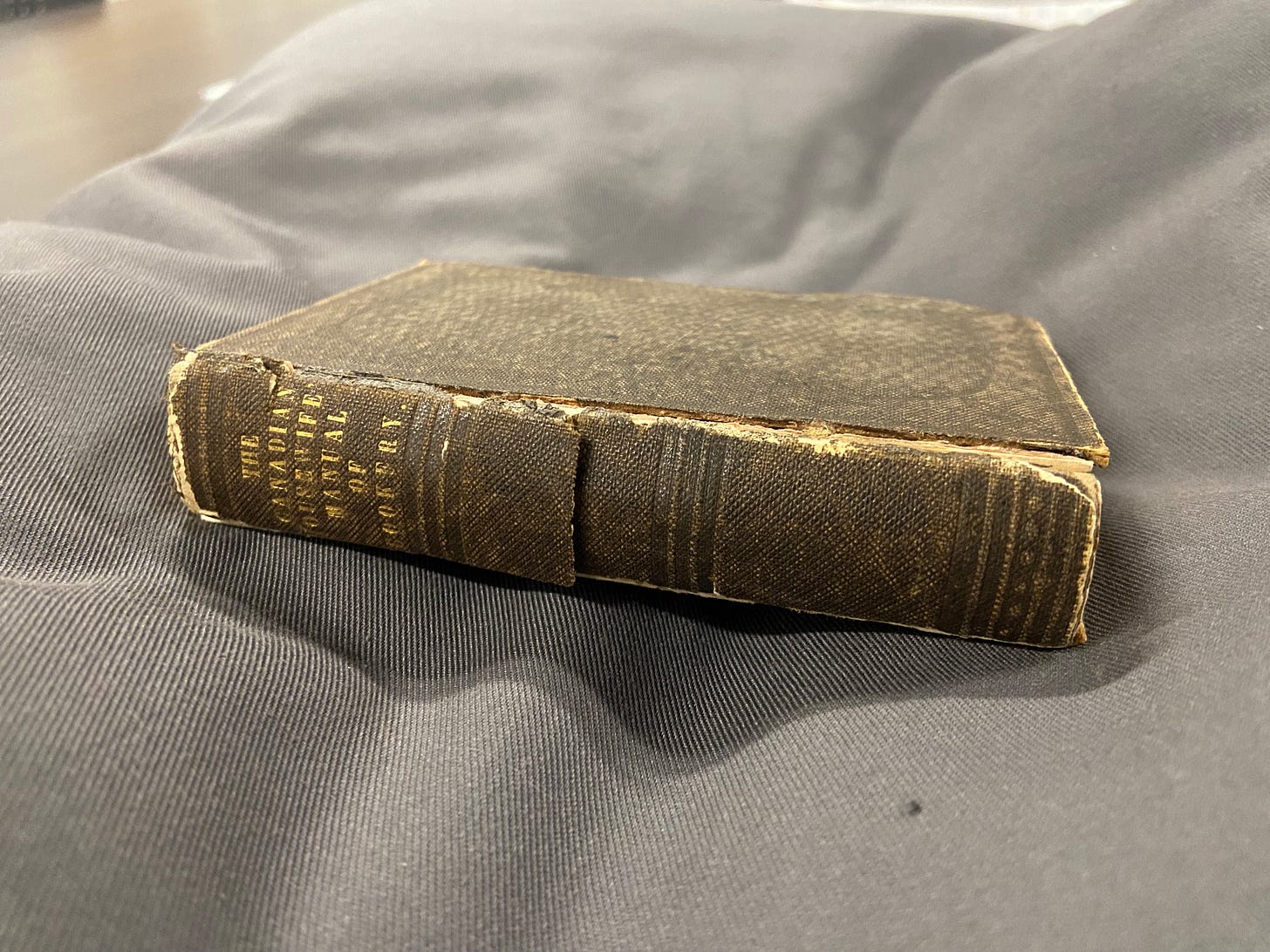

Hamilton’s First Cookbook in Culinary Chronicles

I’m extremely proud of a piece I wrote about the first cookbook to be published in Hamilton, Ontario, which appeared in the Culinary Historians of Canada’s journal. It is rigorously researched and extensively cited, and I was so excited to have my work edited by Fiona Lucas, one of Canada’s preeminent culinary historians.

You can read a short excerpt here, or you can find the whole piece in Culinary Chronicles, Occasional Papers of the Culinary Historians of Canada, New Series, Issue 4, Fall 2024, here; the issue costs CAD $10.

Welcome back, Grace! Loved this. I've enjoyed seeing all the turtles around here this spring. In the very very early spring, I saw an enormous godzilla of a turtle making her way across a frozen pond - pretty unforgettable, pretty wonderful.

Every turtle a soup...loved this, Grace. A lovely mix of many times.